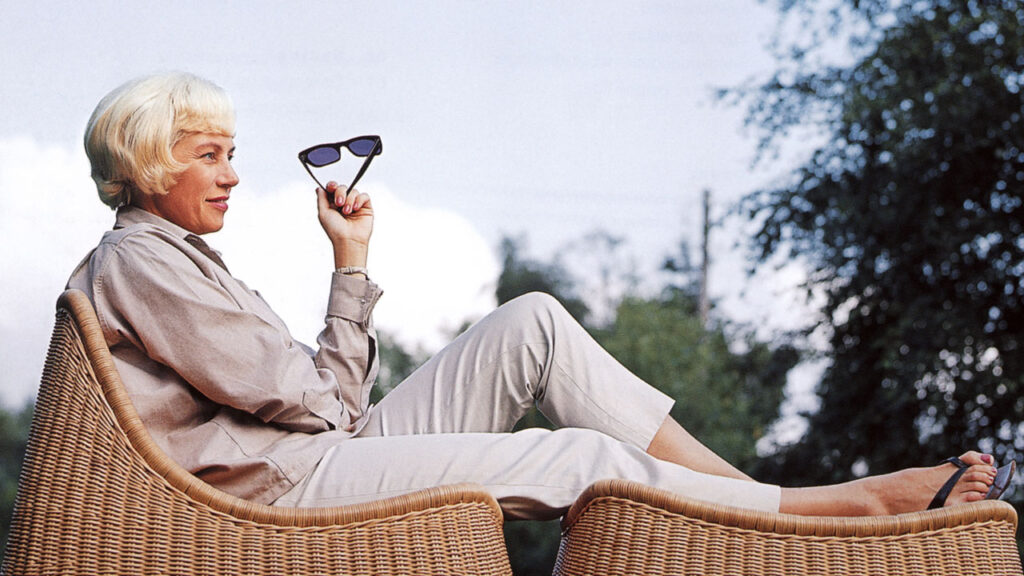

On June 24, 2005, The Guardian published an obituary grieving the death of Nanna Ditzel, and celebrating her contribution to Danish and global design. The article described her as “a leading member of the generation of designers who created the postwar Danish modern movement.” The publication also recognized her “for being a woman in the male-dominated world of industrial design.” For the next fifteen odd years, Nanna Ditzel was nowhere to be found; neither in mainstream media nor in design fairs. She seemed forgotten! There were slight references here and there, but none truly justified the legacy she had left behind.

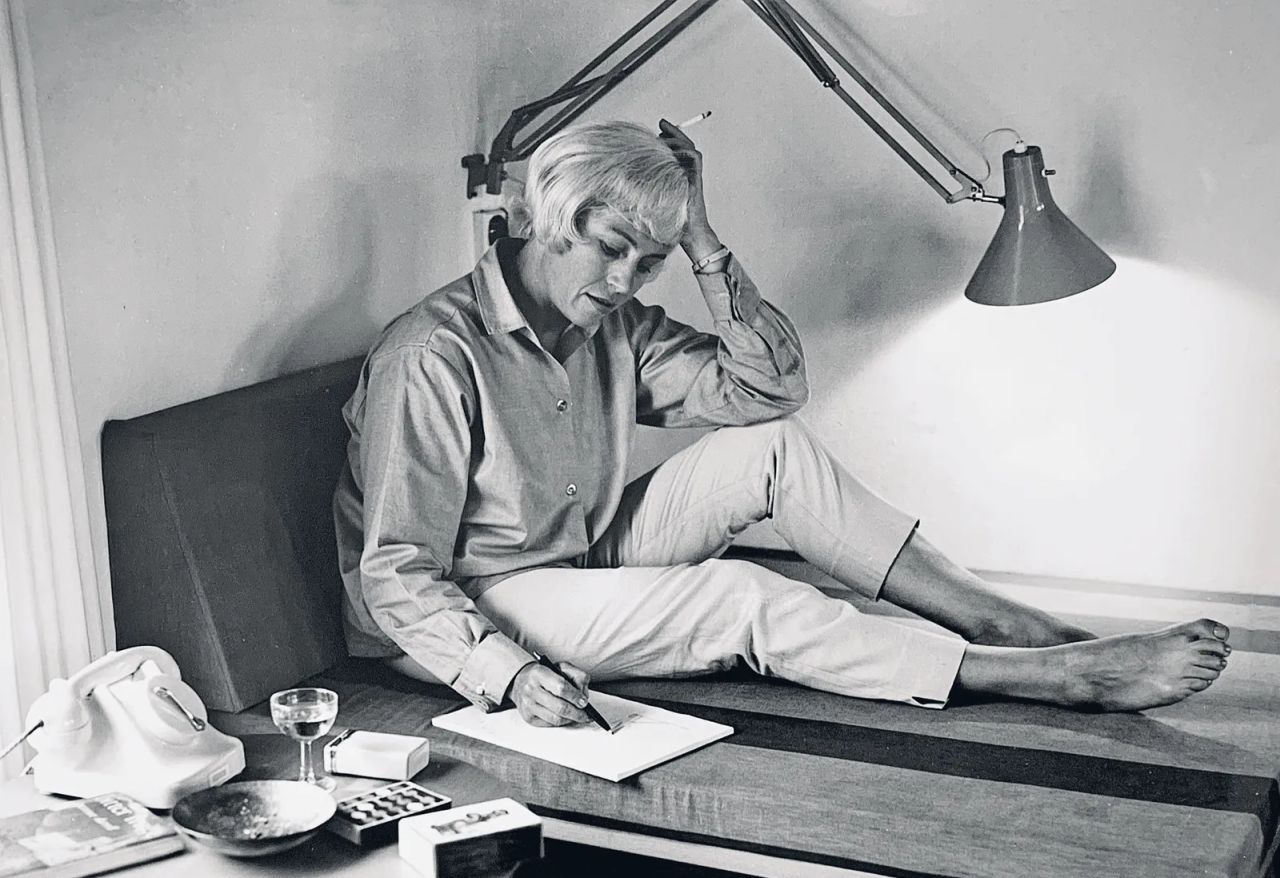

A lady who was once considered the ‘punk woman of Danish design’ and ‘unhailed rebel’ was largely forgotten by Denmark and, by extension, the world. Not because she held a cigarette in one hand and a pen in the other, or because her ideology was different from most designers back then. “She was forgotten probably because she was a woman,” argues Anders Byriel, CEO of Danish textile brand Kvadrat. Thomas Graversen, another significant design entrepreneur, took no time in nodding to the fact and stating, “Ditzel deserved to be counted amongst Danish design icons such as Hans J Wegner, Arne Jacobsen and Verner Panton.” But such was the irony that, forget being counted amongst Danish design icons, she was not even talked about.

It’s the same Denmark that proudly hosts 3daysofdesign, and has long hailed itself as the protector of the culture, craftsmanship throughout the years. But when it came to recognizing Nanna Ditzel, etching her name in the annals of design history, the world and Denmark saw a ‘woman’ tag associated with her.

Homecrux got in touch with Nanna’s granddaughter Camilla Ditzel to reflect on this sentiment and get a glimpse of the personal and professional legacy of a woman who reshaped modern furniture with her bold, nature-inspired creations.

“Nanna was a very warm person to be in company with, and there was a feeling of luxury in each moment spent with her,” her granddaughter recalls. “Despite a busy career that took her across the globe, Nanna always spared time for us, leaving a sense of wonder in our lives. Those moments, filled with love and creativity, left an indelible mark on my life,” she states.

Growing up in the shadow of such a luminary, Camilla’s childhood was steeped in the world of design. “During some of my childhood, Nanna lived in London and that opened my eyes to a world outside little Denmark,” she shares. Visits to Nanna’s eclectic London townhouse, adorned with her iconic glassfibre furniture, and her charming countryside cottage introduced a young girl to a universe where creativity knew no bounds. These spaces, alive with 1960s flair, sparked a lifelong appreciation for bold aesthetics.

Nanna’s influence extended far beyond her home, shaping her granddaughter’s very perception of the world. “Nanna has shaped my way of looking at colours,” she explains. “I get in a good mood when I enter a place where I see bright colours. It makes my brain happy in a confident way.”

“While Nanna Ditzel is not entirely forgotten, her contributions to Danish design are arguably overlooked, especially when compared to her male contemporaries,” she argues. Nevertheless, Nanna Ditzel’s designs, renowned for their timeless blend of function and beauty, continue to resonate in today’s fast-evolving design landscape. “I think the designs speak for themselves,” her granddaughter asserts. “When function and aesthetic work well together, the result is an object that feels timeless—like it has always belonged and always will.” This philosophy, rooted in Nanna’s ability to marry practicality with avant-garde artistry, ensures her work remains as relevant now as it was decades ago.

Certain pieces hold a special place in Camilla’s heart that were an integral part of her childhood. “I’m particularly fond of the Hallingdal 65 textile, probably because I’ve been sitting on it since I was a little girl,” she says. The Mondial series of chairs and sofas, a staple in Nanna’s own home, also carries deep personal resonance. These designs are more than furniture; they are touchstones of memory and connection.

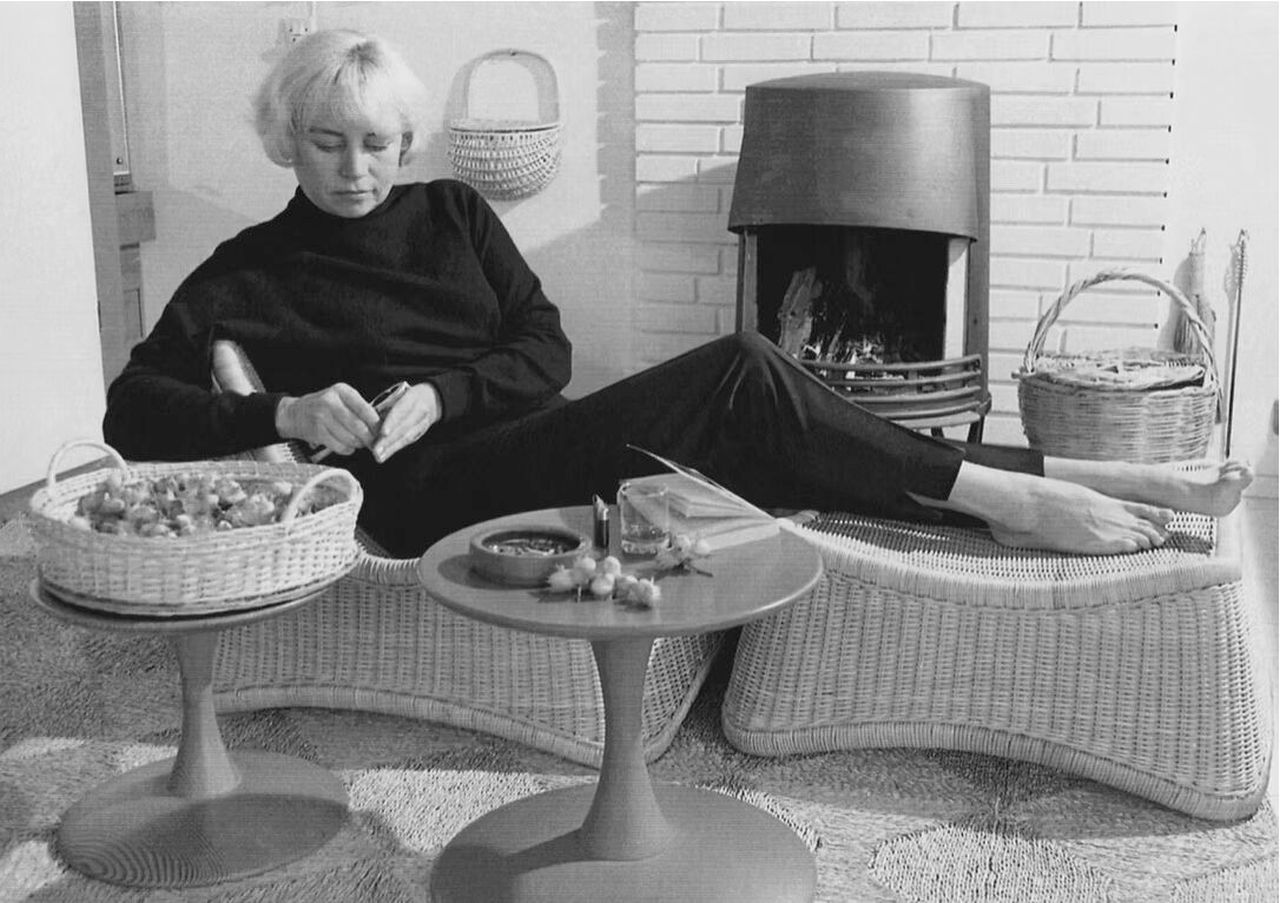

While the world continues to debate where Nanna got her design ideas and inspiration from. Her granddaughter suggests it was a profound respect for nature’s organic forms that found a medium in her design. “Nanna always looked at what was around her,” her granddaughter explains. “She found many of her inspirations in Nature. She once said to my mother, who had asked her why her designs were so rounded, ‘Look out of the window, my girl, out there in Nature you will find no right angles.”

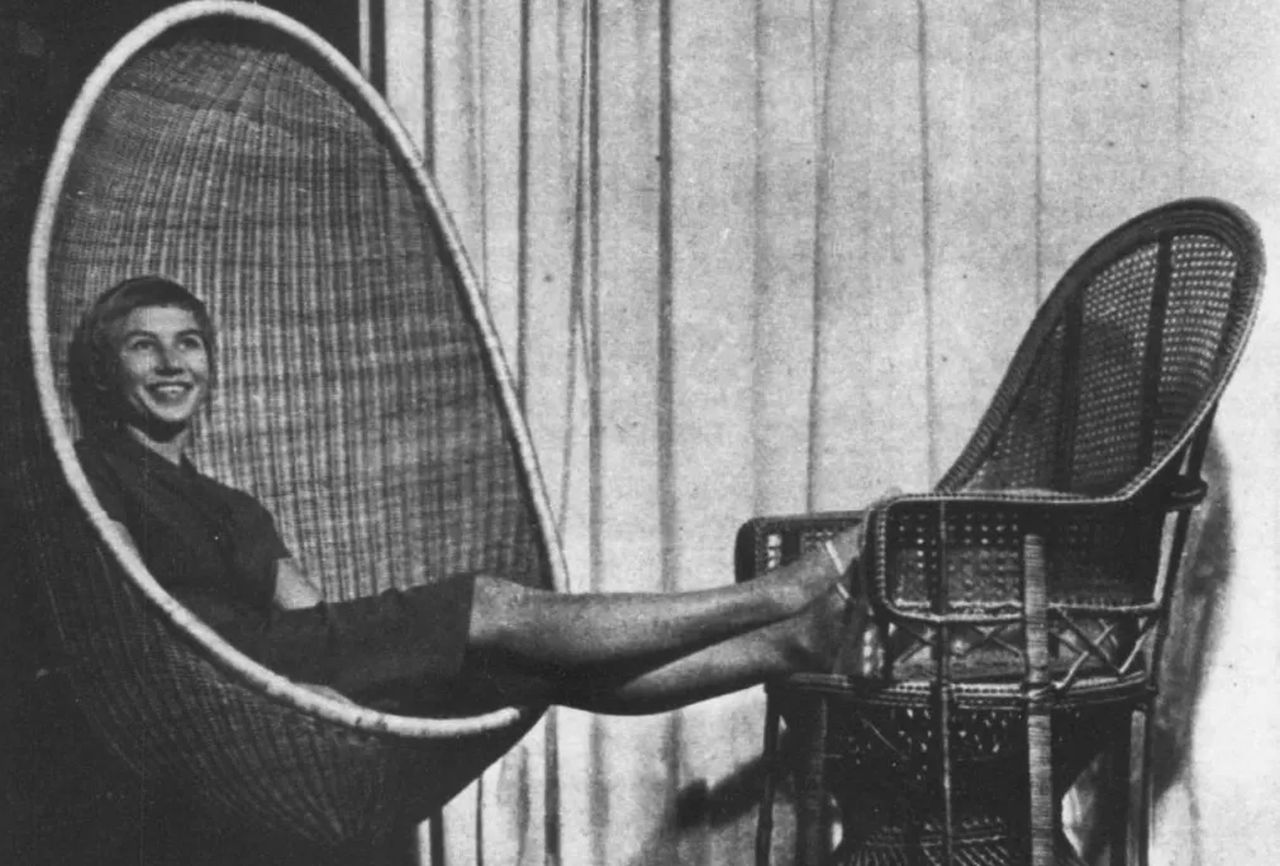

This philosophy is evident in pieces like the Seashell chair and The Bench for Two, where fluid lines evoke the natural world. Nanna’s approach was boundless, as she once declared, “When I start working on a new chair, everything is possible, and everything is allowed. It’s a challenge.” Nanna’s boundary-pushing spirit was perhaps most evident in her iconic designs like the Hanging Egg Chair and the Toadstool series. “When Nanna challenged the traditional design norms, I’m sure it had a lot to do with her view on how we humans should be together,” her granddaughter reflects.

The Hanging Egg Chair, with its cocoon-like embrace, encouraged freer, more dynamic interactions, breaking away from the stiff conventions of traditional seating. Similarly, the Toadstool series, designed for children, rejected miniature adult furniture in favor of playful, functional pieces that invited movement and imagination.

When it came to personal life, Nanna’s creative synergy with her first husband, Jørgen Ditzel, was a cornerstone of her early career. “Nanna and Jørgen were true partners, seamlessly passing designs back and forth during the creative process,” her granddaughter recounts. Their collaborative spirit, fueled by curiosity and a refusal to compromise on comfort, broke new ground in Danish design. By entering competitions and drawing inspiration from their travels, they crafted functional yet boundary-defying pieces that challenged conventions and invited people to embrace the new.

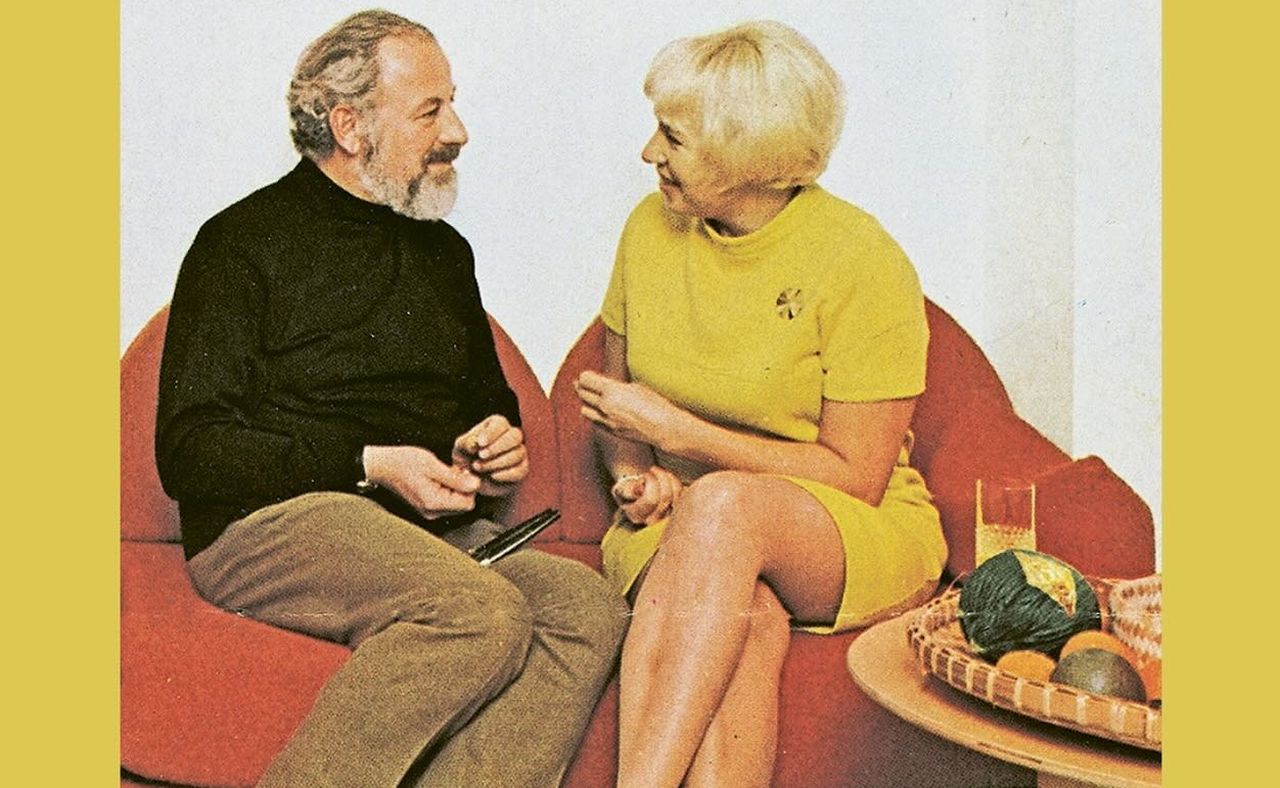

After Jørgen’s passing in 1961, Nanna’s resilience shone through. “Nanna decided that she wanted to continue alone, she felt she owed it to Jørgen,” her granddaughter says. Later, her partnership with her second husband, Kurt Heide, marked a new chapter. Together, they launched Interspace in London, a showroom blending Nanna’s designs with Italian furniture. Even after Kurt’s death, Nanna’s creative drive never wavered. At 63, she returned to Denmark and established a new studio in Copenhagen, a testament to her unyielding passion. “Her relentless drive to create was so innate that it always found a way to flourish,” her granddaughter explains.

In their final moments together, Nanna’s granddaughter witnessed her grandmother’s grace and acceptance. “In the end, it was time to say goodbye, and she was very honest one day and said, among other things, that if it really was her time now, it was okay because she had experienced and done what she was meant to,” she recalls. These words encapsulate a life lived fully, a legacy of creativity, courage, and connection that continues to inspire.

“I am the CEO at Nanna Ditzel Design today,” Camilla says, reflecting on the privilege of succeeding her mother, Dennie Ditzel, in this mission. With greater roles come greater responsibility, and Camilla Ditzel is playing a pivotal role in preserving and promoting a legacy that spans decades. The studio’s recent foray was at 3daysofdesign, where, in collaboration with Fredericia, they presented Nanna’s iconic piece ‘Bench for Two’

The role is not without its challenges, from refining designs with collaborators to ensuring each piece honors Nanna’s vision. Yet, as she notes, “In a way that is what makes the job interesting.” Working alongside colleague Henriette Noermark, she navigates the complexities of keeping a legendary portfolio alive, ensuring every reissue or new project captures the essence of Nanna’s genius.

Follow Homecrux on Google News!